Afr. J. Parasitol. Mycol. Entomol. 2023, 1(1), 3; doi:10.35995/ajpme1010003

Article

Blastocystis sp. Infection in Gabon: Prevalence and Association with Sociodemographic Factors, Digestive Symptoms and Anaemia

Department of Parasitology-Mycology-Tropical Medicine, Faculté de Médecine de l’Université des Sciences de la Santé, Libreville 4009, Gabon

*

Corresponding author: mbondoukwenoe@gmail.com; Tel.: +24174122125

How to Cite: M’Bondoukwé, N.P.; Mawili Mboumba, D.P.; Batchy Ognagosso, F.B.; Moutongo, R.; Ndong Ngomo, J.M.; Koumba Lengongo, J.V.; Mbang Nguema, O.A.; Pongui Ngondza, B.; Bouyou-Akotet, M.K. Blastocystis sp. Infection in Gabon: Prevalence and Association with Sociodemographic Factors, Digestive Symptoms and Anaemia. Afr. J. Parasitol. Mycol. Entomol., 2023, 1(1): 3; doi:10.35995/ajpme1010003.

Received: 15 September 2022 / Accepted: 17 May 2023 / Published: 12 June 2023

Abstract

:Introduction: Blastocystis sp. is an intestinal protozoan that is commonly reported, but whose clinical significance remains controversial. Clinical forms of this infection range from asymptomatic carriage to clinical signs, specifically gastrointestinal ones. There is a lack of data on the epidemiology of this protist in Gabon. This study was carried out to provide data on the frequency of Blastocystis sp. infection and its association with clinical signs and the haemoglobin rate. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted between September 2018 and November 2019. Stool samples were collected in five of the nine provinces of Gabon from children and adults. Sociodemographic and clinical data were recorded using a standardised pre-tested questionnaire. Haematological parameters and temperature were reported in a laboratory register. Parasitological diagnosis was performed using stool direct examination and a Merthiolate-Iodine-Formaldehyde (M.I.F) concentration to detect Blastocystis sp. Results: In total, 843 participants were interviewed and examined; 414 brought back stool samples. The frequency of Blastocystis sp. infection was 45.2% (n = 187/414), and it increased with age: from 20.0% in young children to 49.5% in adults (P = 0.0057). Being a male (P = 0.08) tended to be associated with Blastocystis sp. carriage. In the multivariate logistic regression, only males were associated with Blastocystis sp. infection and had a 4.3-fold higher risk of being infected than females did (adjusted odds ratio = 4.3; 95% CI = 1.2–15.6; P = 0.03). Diarrhoea, abdominal pain and colitis were observed in some patients with Blastocystis sp. monoinfection. No relation between Blastocystis sp. carriage and anaemia was found. Conclusion: The frequency of Blastocystis sp. infection was high. Males were more at risk of being infected. Blastocystis sp. could be used as indicator in the improvement of environmental sanitation and hygiene, coupled with improved housing. Additional investigations in a population with clinical symptoms should be performed.

Keywords:

Blastocystis sp.; monoinfection; Gabon; risk factors; clinical signs; anaemia1. Introduction

Blastocystis sp. is a unicellular, eukaryotic, anaerobic protist that is detected in the gut of many hosts, such as birds and mammals. It is the most common intestinal parasite found in human faeces, whatever their age [1]. This stramenopile has a wide polymorphism according to size and form: it has vacuolar (the most recognised form using a light microscope), amoeboid, granular and cysts forms.

This parasite has been reported worldwide. In 2006, Blastocystis sp. was introduced in the list of water-borne parasites by the World Health Organization and was found in one billion of people throughout the world [2].

Blastocystis sp. is considered to be a commensal organism due to the asymptomatic carriage reported among populations [3]. However, evidence attribute to this protist clinical symptoms, such as pruritus, colitis, diarrhoea, irritable bowel syndrome, and also, colorectal cancer [4,5,6].

In developing countries, the burden of Blastocystis sp. infection may reach 60.0% or more [7]. In these countries, the risk factors related to the faecal–oral transmission of Blastocystis sp. have been identified, such as age, poor sanitation, being in close contact with animals, the consumption of contaminated drink and/or food, the use of latrines, living with infected persons, having a low household income and parents’ education [7,8,9,10,11]. The tropical climate is also correlated with a high prevalence of this parasite [12]. In Malaysian villages, the protist has been found in water [13].

In Gabon, a retrospective study performed between 2004 and 2014 showed an increase in the prevalence of Blastocystis sp., ranging from 0.7 to 45.6% among symptomatic individuals. Indeed, some previous studies reported the high prevalence of Blastocystis sp.-infected individuals, 41.6% and 48.6%, among populations living in rural areas and in shanty towns of Libreville, respectively [1,14,15,16]. Many neighbourhoods lack water supplies in Libreville, the capital city of Gabon, exposing populations to faecal–oral transmission and to Blastocystis sp. infection. However, the relationship between the presence of this parasite and clinical symptoms was not investigated in the country.

Furthermore, a lower rate of haemoglobin among individuals infected with Blastocystis sp. has been reported [17,18,19]. Anaemia is an important public health problem in Gabon [20]. It affects 62.5% and 58.9% of young children and non-pregnant women aged 15-49 years old, respectively (https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/gabon/prevalence-of-anemia). The impact of malaria and intestinal helminthiasis, such as Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura and Necator americanus, on anaemia occurrence have been described, but no researchers have investigated that of Blastocystis sp. [21,22]. Thus, the aim of the present study was to assess the relationship between Blastocystis sp. infection, sociodemographic factors, clinical signs and the haemoglobin rate.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Sites, Period and Populations

A cross-sectional study was conducted from September 2018 to June 2019 in five out of the nine provinces of Gabon in sites where a project on the epidemiology of malaria/helminthiasis/intestinal protozoan coinfection was conducted [1,23]. Populations living in areas with different levels of urbanization, urban, suburban and rural areas, were recruited. Socioeconomic, demographic and clinical data were collected during face-to-face interviews with populations and reported using a standardised case report form. Each participant brought a single stool sample, as recommended by the study staff. Infections with intestinal parasites, malaria and filariasis were also recorded. Axillary temperature (°C) and haemoglobin rate (g/dL) when available, and parasitological data were reported using the case report form. The haemoglobin rate was measured using the Hemocue Hb 201+ Analyzer (Ängelholm, Sweden). Thick and thin blood smears and nested PCR were performed for the detection of Plasmodium sp. infection [24,25]. Direct blood examination and the leukoconcentration technique, direct stool examination, Merthiolate-Iodine-Formaldehyde coloration and concentration tests were performed for filariasis and intestinal parasites infections diagnosis, respectively, as previously described [1,14].

2.2. Procedures of Data Selection

The database was created on Microsoft Excel® using data obtained from the case report forms of each participant. Double data entry was performed by two independent operators. After data cleaning, the database was duplicated: one version was conserved, and the second one was re-opened and modified for the present study.

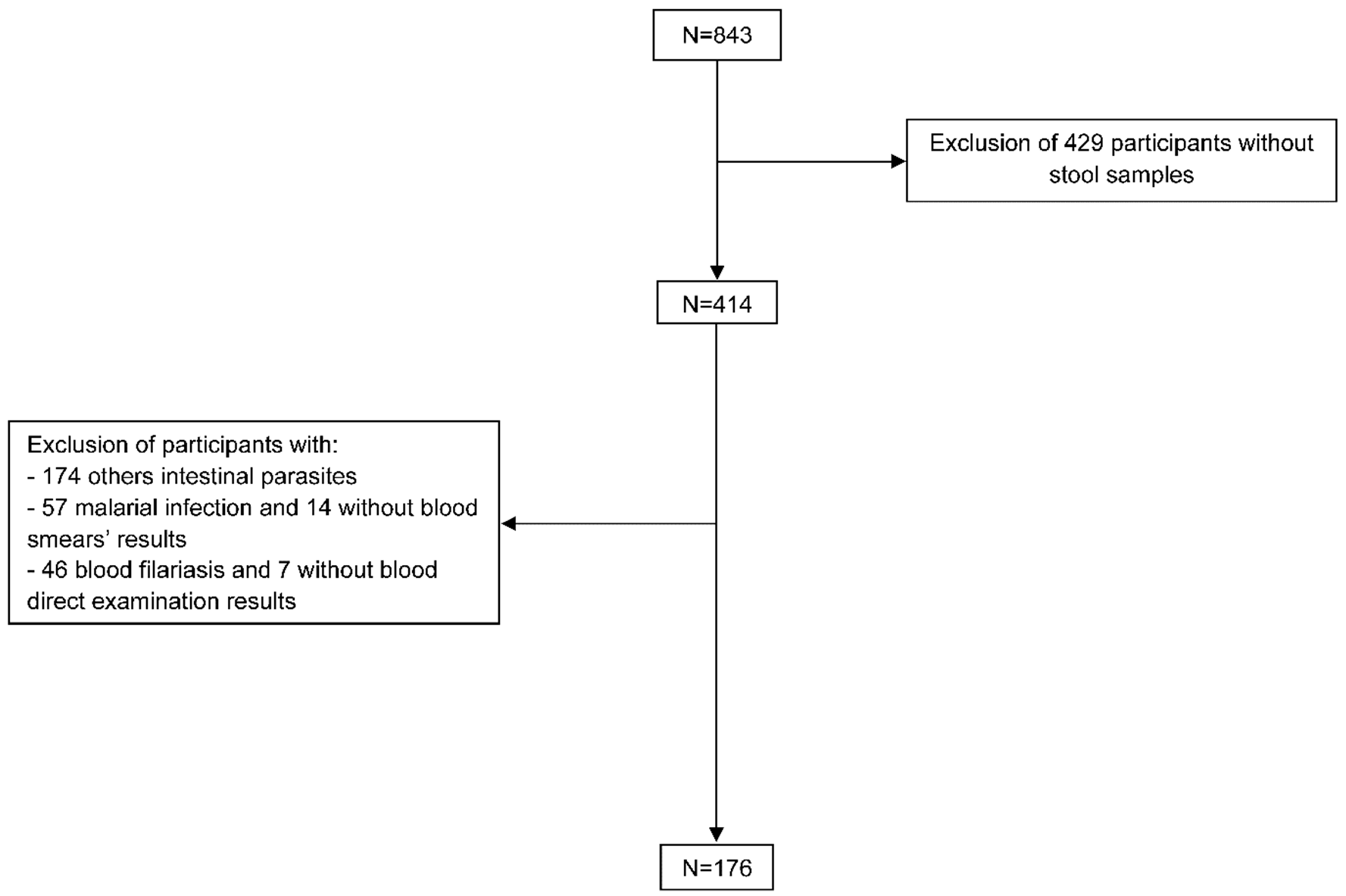

Data from participants found with malaria, blood filariasis and intestinal parasites other than blastocystosis and co-infections were not considered to avoid bias (Figure 1).

2.3. Ethics

This study received ethical clearance from “Comité National d’Ethique pour la Recherche” (CNER) of Gabon PROT No 003/2016/SG/CNE. The protocol and the questionnaire were also approved by the Ministry of Health. Infected patients were treated according to the national guidelines.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Statview 5.0 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R v4.3.2 software. Qualitative variables such as “gender”, “age groups”, “locations”, “marital status”, “illiteracy”, “education level”, “type of house”, “occupation”, “type of toilet”, “open water body near home”, “regular wearing of shoes when outside”, “source of drinking water”, “fever”, “digestive symptoms”, “anaemia”, “type of anaemia” and “Blastocystis sp. monoinfection” are presented in percentages (%). Quantitative variables were examined for normal distribution and kurtosis and skewness in applied parametric or non-parametric tests. The quantitative variables, “temperature” and “haemoglobin level”, followed a normal distribution, and are presented as means (± standard deviation). Participants were categorised by age into less than 5 years old, 5-15 years and more than 15 years old under the “age groups” variable. The sex ratio (male/female) was calculated. Populations were distributed among four groups according to the haemoglobin rate: absence of anaemia, mild anaemia, moderate anaemia and severe anaemia (https://www.who.int/vmnis/indicators/haemoglobin.pdf). The “temperature” variable was transformed into a binary variable; those with a fever were placed in the “yes” group if the value was above of 37.5 °C or the “No” group if it was below this.

The comparison of Blastocystis sp. infections according to the characteristics of the population was performed with Pearson’s Chi2 test, and haemoglobin rates and temperatures were compared with Student’s t-test.

Crude odds ratios (cORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to assess the association between “Blastocystis sp” monoinfection and “gender”, “age groups”, “locations”, “marital status”, “illiteracy”, “education level”, “type of house”, “occupation”, “type of toilet”, “open water body near home”, “wearing of shoes”, “source of drinking water”, “digestive symptoms”, “anaemia” and “type of anaemia”. Logistic regression was performed to estimate the adjusted odds ratios (aOR) between “gender”, “age groups”, “locations” and “marital status” and those with a P value <0.20 in the bivariate analysis. A P value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

During the study, 843 participants were enrolled and interviewed; among them, 414 brought back stools samples (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study population selection. This figure shows the selection process of the study population. First, participants with no stool samples were excluded. After this, we were left with all participants infected with other parasites: intestinal parasites infection, malaria and blood filariasis. Additionally, individuals who did not provide results of the biological test were excluded.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study population selection. This figure shows the selection process of the study population. First, participants with no stool samples were excluded. After this, we were left with all participants infected with other parasites: intestinal parasites infection, malaria and blood filariasis. Additionally, individuals who did not provide results of the biological test were excluded.

The characteristics of participants (n = 414) whose brought back stool samples were examined, as summarised in Table 1. The rate response to the questionnaire items ranged from 61.4% (n = 254/414) to 97.3% (n = 403/414). Nearly two-thirds of the participants were older than 15 years (62.6%; n = 234/374). Female participants were predominant; the sex ratio was 0.7. Three quarters of the participants lived in rural areas (75.1%; n = 268/357) and 40.1% were single (n = 130/324). During the interview, 17.5% (n = 26/320) declared themselves to be illiterate, 7.4% (n = 23/312) had no education qualification, and almost half of the study population was unemployed (44.4%; n = 119/298). Regarding lifestyle, more than 2/3 (68.6%; n = 177/258) lived in a wood house or in a sheet metal house or in an earthen house. In addition, more than one third of the participants used non-conventional latrines (40.5%; n = 120/296), lived near of an open water body (40.1%; n = 107/267) and did not wear shoes regularly outside (39.5%; n = 106/268). Likewise, when both “spring” and “river” water consumption were considered, almost one-third of the participants had drunk unsafe water (30.7%; n = 78/254).

Among the febrile patients or those with a history of having a fever (56.4%; n = 84/149), the mean temperature was 37.8 ± 1.2 °C. The mean rate of haemoglobin was 10.6 ± 2.2 g/dL, and anaemia was reported in 64.6% (n = 93/144) of the participants. Moderate anaemia was predominant (44.4%; n = 64/144).

3.2. Blastocystis sp. Infection Frequency

The frequency of Blastocystis sp. infection was 45.2% (n = 187/414). Table 1 shows that among the patients with or without Blastocystis sp. monoinfection only (n = 176), men (P = 0.08) tended to be more frequently infected. Blastocystis sp. monoinfection was significantly associated with the age: it increased from 20.0% among children aged less than 5 years old to 49.5% among individuals that were more than 15 years old (P = 0.0057).

3.3. Association between Temperature, Haemoglobin Level and Blastocystis sp. Monoinfection

The mean temperatures were comparable among patients with Blastocystis sp. monoinfection (37.8 ± 1.1 °C) and uninfected ones (38.0 ± 1.1 °C) (P = 0.4). Infected patients had a higher level of haemoglobin (10.8 ± 2.0 g/dL) compared to that of the uninfected patients (9.8 ± 1.9 g/dL) (P = 0.08).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population and distribution of Blastocystis sp. infection

| Overall Population n = 414 | Selected Participants n = 176 | B. sp. Infected Individuals n = 68 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n * | % | n ** | % | n *** | % | P | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age groups | 374 | 161 | 67 | ||||

| <5 years old | 64 | 17.1 | 40 | 24.8 | 8 | 20.0 | |

| 5–15 years old | 76 | 20.3 | 24 | 15.0 | 11 | 45.8 | |

| >15 years old | 234 | 62.6 | 97 | 60.2 | 48 | 49.5 | 0.0057 |

| Socioeconomic characteristics | |||||||

| Gender | 403 | 172 | 68 | ||||

| Male | 165 | 40.9 | 78 | 45.3 | 37 | 47.4 | |

| Female | 238 | 59.1 | 94 | 54.7 | 31 | 33.0 | 0.08 |

| Locations | 357 | 153 | 58 | ||||

| Urban area | 34 | 9.5 | 24 | 15.7 | 10 | 41.7 | |

| Suburban area | 55 | 15.4 | 33 | 21.6 | 9 | 27.3 | |

| Rural area | 268 | 75.1 | 96 | 62.7 | 39 | 40.6 | 0.36 |

| Marital status | 324 | 142 | 57 | ||||

| Single | 130 | 40.1 | 53 | 37.3 | 26 | 49.1 | |

| Family **** | 194 | 59.9 | 89 | 62.7 | 31 | 34.8 | 0.13 |

| Literacy | 320 | 141 | 56 | ||||

| No | 56 | 17.5 | 20 | 14.2 | 7 | 35.0 | |

| Yes | 264 | 82.5 | 121 | 85.8 | 49 | 40.5 | 0.8 |

| Education level | 312 | 139 | 56 | ||||

| No education | 23 | 7.4 | 11 | 7.9 | 2 | 18.2 | |

| Primary school | 123 | 39.4 | 46 | 33.1 | 20 | 43.5 | |

| Middle school | 148 | 47.4 | 71 | 51.1 | 31 | 43.7 | |

| High school | 18 | 5.8 | 11 | 7.9 | 3 | 27.3 | 0.3 |

| Type of house | 258 | 101 | 41 | ||||

| Brick house | 59 | 22.9 | 33 | 32.7 | 13 | 40.6 | |

| Wood house | 155 | 60.1 | 51 | 50.5 | 19 | 37.2 | |

| Mixed house | 22 | 8.5 | 9 | 8.9 | 6 | 60.0 | |

| Sheet metal house | 7 | 2.7 | 3 | 3.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Earthen house | 15 | 5.8 | 5 | 4.9 | 3 | 60.0 | 0.2 |

| Occupation | 298 | 116 | 44 | ||||

| Middle manager | 43 | 16.1 | 22 | 19.0 | 6 | 27.3 | |

| Senior manager | 7 | 2.6 | 4 | 3.4 | 2 | 50.0 | |

| Employee | 86 | 32.1 | 42 | 36.2 | 21 | 50.0 | |

| Unemployed | 119 | 44.4 | 45 | 38.8 | 15 | 33.3 | |

| Retired | 13 | 4.8 | 3 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Type of toilet | 296 | 110 | 44 | ||||

| Modern | 133 | 45.0 | 45 | 40.9 | 13 | 28.9 | |

| Non-conventional latrine | 120 | 40.5 | 63 | 57.3 | 30 | 47.6 | |

| Conventional latrine | 43 | 14.5 | 2 | 1.8 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.1 |

| Open water body near home | 267 | 112 | 44 | ||||

| Yes | 107 | 40.1 | 53 | 47.3 | 23 | 43.4 | |

| No | 160 | 59.9 | 59 | 52.7 | 21 | 35.6 | 0.5 |

| Regular wearing of shoes when outside | 268 | 113 | 45 | ||||

| Yes | 162 | 60.5 | 69 | 61.1 | 27 | 39.1 | |

| No | 106 | 39.5 | 44 | 38.9 | 18 | 40.9 | 1.0 |

| Source of drinking water | 254 | 111 | 44 | ||||

| Spring | 21 | 8.3 | 8 | 7.2 | 3 | 37.5 | |

| River | 48 | 18.9 | 11 | 9.9 | 5 | 45.4 | |

| Tap | 176 | 69.3 | 88 | 79.3 | 34 | 38.6 | |

| River+tap | 7 | 2.7 | 2 | 1.8 | 2 | 100.0 | |

| Spring+tap | 2 | 0.8 | 2 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| Clinicobiological characteristics | |||||||

| Fever | 149 | 69 | 21 | ||||

| Yes | 84 | 56.4 | 43 | 62.3 | 10 | 23.2 | |

| No | 65 | 43.6 | 26 | 37.7 | 11 | 42.3 | 0.16 |

| Digestive symptoms | 77 | 26 | 7 | ||||

| Yes | 37 | 48.1 | 17 | 65.4 | 5 | 29.4 | |

| No | 40 | 51.9 | 9 | 34.6 | 2 | 22.2 | 1.0 |

| Anaemia | 144 | 38 | 10 | ||||

| Yes | 93 | 64.6 | 29 | 76.3 | 8 | 27.6 | |

| No | 51 | 35.4 | 9 | 23.7 | 2 | 22.2 | 1.0 |

| Type of anaemia | 144 | 38 | 10 | ||||

| No | 51 | 37.0 | 9 | 23.7 | 2 | 22.2 | |

| Mild | 64 | 44.4 | 25 | 65.8 | 7 | 28.0 | |

| Moderate | 25 | 17.4 | 3 | 7.9 | 1 | 33.3 | |

| Severe | 4 | 2.8 | 1 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

* indicates the number of participants who brought back stool samples; ** number of participants after the exclusion of patients with malarial infection, blood filariasis and other intestinal parasites than Blastocystis sp.; *** Blastocystis sp.-infected participants; **** family: both parents lived with the children included in the study.

3.4. Digestive Symptoms and Frequency of Blastocystis sp.

The presence or absence of digestive symptoms was reported for 77 participants who underwent the stool examination, but in 3 cases, the symptoms were not specified. Less than half had digestive symptoms (45.9%; n = 34/74). Colitis was frequent (32.4%; n = 24/74), followed by abdominal pain (28.4%; n = 21/74) and diarrhoea (17.6%; n = 13/74) (Table 2). Out of 34 participants who had digestive symptoms, diarrhoea (20.6%; n = 7/34) was the predominant clinical sign, and abdominal pains were less frequently reported (8.8%; n = 3/34) among those with a single symptom. Among the patients with more than one clinical symptom, the association between colitis and abdominal pains was most frequently observed (38.2%; n = 13/34) (Table 2).

No relationship was established between the presence of digestive symptoms and Blastocystis sp. infection (P > 0.05). Out of the 26 with known digestive symptoms, 7 carried this parasite. One patient had diarrhoea only, colitis associated with abdominal pains was reported in three patients, and one other participant presented with colitis, abdominal pains and diarrhoea. Blastocystis sp. was not found in patients with rectal pain (Table 2).

Table 2.

Digestive symptoms reported by the study population and relationship with blastocystosis.

| Overall Population n = 414 | Selected Participants n = 176 | B. sp.-Infected Individuals n = 68 | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digestive symptoms | N = 74 * | % | N = 26 | % | N = 7 | % | |

| Colitis | |||||||

| Yes | 24 | 32.4 | 13 | 50.0 | 4 | 30.8 | |

| No | 50 | 68.6 | 13 | 50.0 | 3 | 23.1 | 1.0 |

| Abdominal pains | |||||||

| Yes | 21 | 28.4 | 9 | 34.6 | 4 | 44.4 | |

| No | 53 | 72.6 | 17 | 65.4 | 3 | 17.6 | 0.3 |

| Diarrhoea | |||||||

| Yes | 13 | 17.6 | 7 | 26.9 | 2 | 28.6 | |

| No | 61 | 83.4 | 19 | 73.1 | 5 | 26.3 | 1.0 |

| Rectal pains | |||||||

| Yes | 1 | 1.3 | 1 | 3.8 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| No | 73 | 98.7 | 25 | 96.1 | 7 | 28.0 | 1.0 |

| Association of digestive symptoms | N = 34 | % | N = 17 | % | N = 5 | % | P |

| 1 symptom | |||||||

| Abdominal pains only | 3 | 8.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Colitis only | 4 | 11.8 | 3 | 17.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Diarrhoea only | 7 | 20.6 | 4 | 23.5 | 1 | 25.0 | |

| 2 symptoms | |||||||

| Colitis+diarrhoea | 2 | 5.9 | 1 | 5.9 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Colitis+abdominal pains | 13 | 38.2 | 6 | 35.3 | 3 | 50.0 | |

| 3 symptoms | |||||||

| Colitis+abdominal pains+diarrhea | 4 | 11.8 | 2 | 11.8 | 1 | 50.0 | |

| Colitis+abdominal pains+rectal pains | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 5.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.5 ** |

* indication of the digestive symptom was missing for 3 patients; ** P value for the association of digestive symptoms.

3.5. Risk factors of Blastocystis sp. monoinfection

Bivariate analysis identified two at-risk factors associated with Blastocystis sp. monoinfection: being more than 15 years old (cOR = 3.9; 95% CI = 1.6–9.4; P = 0.002) and being 5–15 years old (cOR = 3.4; 95% CI = 1.1–10.3; P = 0.03). Being a male (cOR = 1.8; 95% CI = 0.9–3.4; P = 0.05), being single (cOR = 1.8; 95% CI = 0.9–3.6; P = 0.09), being an employee versus a middle manager (cOR = 2.7; 95% CI = 0.9–8.1; P = 0.08) and having a fever (cOR = 2.4; 95% CI = 0.8–6.9; P = 0.099) tended to be at-risk factors (Table 3).

In the multivariate analysis performing using logistic regression, being a male was a risk factor of Blastocystis sp. infection (aOR = 4.3; 95% CI = 1.2–15.6; P = 0.03) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk factors among populations with only Blastocystis sp. infection.

| Blastocystis sp. infection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | cOR (95% CI) | P | aOR (95% CI) | P |

| Gender | ||||

| Male vs. female | 1.8 (0.9–3.4) | 0.05 | 4.3 (1.2–15.6) | 0.03 |

| Age groups | ||||

| >15 years old vs. < 5 years old | 3.9 (1.6–9.4) | 0.002 | 2.1 (0.3–13.6) | 0.4 |

| [5–15] years old vs. < 5 years old | 3.4 (1.1–10.3) | 0.03 | 2.3 (0.5–10.8) | 0.3 |

| Location | ||||

| Rural area vs. Suburban area | 1.8 (0.7–4.3) | 0.17 | 0.6 (0.08–4.7) | 0.6 |

| Urban area vs. Suburban area | 1.9 (0.6–5.8) | 0.26 | 2.2 (0.5–9.5) | 0.3 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single vs. Family | 1.8 (0.9–3.6) | 0.09 | 1.1 (0.3–4.1) | 0.9 |

| Illiteracy | ||||

| Yes vs. No | 1.2 (0.5–3.4) | 0.6 | . | . |

| Education level | ||||

| Middle school vs. Primary school | 1.0 (0.5–2.1) | 0.98 | . | . |

| High school vs. Primary school | 0.5 (0.1–2.1) | 0.3 | . | . |

| No education vs. Primary school | 0.3 (0.06–1.5) | 0.1 | . | . |

| Type of house | ||||

| Brick house vs. Earthen house | 0.4 (0.06–2.9) | 0.4 | . | . |

| Wood house vs. Earthen house | 0.4 (0.06–2.6) | 0.3 | . | . |

| Mixed house vs. Earthen house | 1.3 (0.1–12.8) | 0.4 | . | . |

| Occupation | ||||

| Senior manager vs. Middle manager | 2.7 (0.3–23.4) | 0.4 | . | . |

| Employee vs. Middle manager | 2.7 (0.9–8.1) | 0.08 | . | . |

| Unemployed vs. Middle manager | 1.3 (0.4–4.1 ) | 0.6 | . | . |

| Type of toilet | ||||

| Non-conventional latrine vs. Conventional latrine | 0.9 (0.05–15.2) | 0.9 | . | . |

| Modern vs. Conventional latrine | 0.4 (0.02–7.0) | 0.5 | . | . |

| Open water body near home | ||||

| No vs. Yes | 0.7 (0.3–1.5) | 0.4 | . | . |

| Digestive symptoms | ||||

| Yes vs. No | 1.4 (0.2–9.6) | 0.7 | . | . |

| Fever | ||||

| No vs. Yes | 2.4 (0.8–6.9) | 0.099 | . | . |

| Anaemia | ||||

| No vs. Yes | 0.7 (0.1–4.4) | 0.7 | . | . |

| Type of anaemia | ||||

| Mild vs. Moderate | 0.8 (0.06–10.0) | 0.8 | . | . |

4. Discussion

This study is the first one to report the epidemiology of Blastocystis sp. monoinfection in different areas of Gabon and its relationship with sociodemographic data and clinical symptoms in Gabonese populations.

The prevalence of Blastocytis sp. was 45.2%, as previously described among patients consulting at the Department of Parasitology and Mycology among populations living in the 3rd and the 6th districts of Libreville, Gabon [14]. The prevalence was lower in Egypt (26.5–34.5%), Iran (7.0%), Thailand (7.2–27.4%) and Malaysia (10.6–25.7%) [9,10,11,18,19]. However, in Sub-Saharan Africa some authors from the Ivory Coast (58.2%), Nigeria (84.0%), Senegal (100.0%) and in Central Africa, in Cameroon (88.2%), reported a higher prevalence of Blastocystis sp. [26,27,28,29]. In these studies, molecular tools were used for Blastocytis sp. diagnosis that may explain these differences. Indeed, molecular tools are twofold more sensitive than microscopy is for the detection of stramenopile [2,12,30,31]. This observation suggests that the prevalence of Blastocystis sp. infection in Gabon may be underestimated.

Others factors could contribute to the variation in Blastocystis sp. prevalence, such as the presence of symptoms, being old and being HIV-positive according to serology examination [9,11,32]. Indeed, in Equatorial Guinea, a neighbouring country of Gabon, the parasite was more frequently detected among people living with HIV who did not received ART treatment [32]. Blastocystis sp. was also found in Gabon and Ghana among people living with HIV, although less frequently than it was found among HIV-negative participants [15,33].

In the current study, the prevalence of Blastocystis sp. infection increased with age. In surveys performed in Thailand and in Nigeria, similar results were observed [9,28]. These data suggest the role of adults as a reservoir of Blastocystis sp., such as it has been reported for other intestinal pathogens (soil-transmitted nematodes, Giardia intestinalis, Cryptosporidium sp., Isospora belli and Entamoeba histolytica). Indeed, in an orphanage at Chypre, infants living with parasitised adults were more at risk of infection [9]. After adjusting for confounding factors in multivariate analysis, no relationship between age and the carriage of Blastocystis sp. was observed.

On the other side, male had a fourfold higher risk of infection than their female counterpart did. This relationship has not been reported elsewhere [28,34,35]. Multivariate analysis was carried out on a smaller sample size in comparison to that of the population at baseline. Additionally, the following variables, “educational level”, “occupation” and “fever”, were not included in the multivariate analysis due to missing data. It is possible that occupation may be a factor favouring the frequent infection of men. Additionally, other risk factors for blastocystosis was not considered in the present study, such as living with domestic animals or water being treated before consumption [36].

The main intestinal symptom in the current study was abdominal pain, as reported elsewhere, followed by colitis, diarrhoea and rectal pain [37,38]. Others gastrointestinal disorders, such as bloating, constipation, flatulence and vomiting, have also been related to Blastocystis sp. infection [37,38]. However, in Senegal, in Chypre, in Australia and in the present study, no relationship was found between the presence of the parasite and the occurrence of these symptoms [26,30,39].

Blastocystis sp. has been related to anaemia [17,18,19,40,41,42]. An explanation for this may be that Blastocystis sp., such as other enteric parasites, can lead to a possible decrease in the absorption of nutrients in the intestinal mucosa due disturbing leptin and adiponectin levels in children [43]. However, in the present study, anaemia was not related to Blastocystis sp. infection. It is possible that the small sample size may explain these results. Other haematological parameters may be explored, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, the levels of which were found to be higher in cases of Blastocystis sp. infection compared to those of a control group. Inversely, levels of haematocrit, leukocytes, neutrophils were found to be lower [17,41]. This study contains interesting information that shows that Blastocystis sp. can cause inflammation and may have an impact on the immunomodulation of the human host. This should be explored.

5. Conclusion

Blastocystis sp. prevalence in Gabon is high and indicates the poor hygiene and living conditions of populations. The intestinal parasite has been found more frequently among elderly individuals and in the male population, but the analysis was performed on a small sample size, which is the main limitation of the present study. Health education should be implemented in the country to also control soil-transmitted helminthiasis and achieve elimination by 2030. In addition to the risk factors, the identification of knowledge, attitudes and practices via running an adapted sensibilization campaign would have a positive impact on faecal and intestinal parasite transmission. Blastocystis sp., the intestinal parasite that is more prevalent in the country, must be considered as an environmental indicator to assess the efficiency of different integrated strategies that will be deployed in the world.

Author Contributions

M.K.B.-A. was the principal investigator and conceived the study with N.P.M. and D.P.M.-M. N.P.M. collected data in the field; biological sample collections and slides reading were performed by N.P.M., J.V.K.L., R.M., J.M.N.N. and B.P.N. Physical examinations and clinical data processing was performed by F.B.B.O. D.P.M.-M. and N.P.M. wrote the paper. M.K.B.-A. and O.A.M.N. reviewed and edited the paper. The statistical analyses were carried out by N.P.M. and D.P.M.-M. took part in the interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Department of Parasitology and Mycology at the University of Health Sciences and the Gabonese Red Cross.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank you to the Gabonese Red Cross for its participation in the collection of the participants’ data.

Conflicts of Interest

We disclose any financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence (bias) our work.

Abbreviation

There are no non-standard abbreviations.

References

- M’Bondoukwé, N.P.; Kendjo, E.; Mawili-Mboumba, D.P.; Koumba Lengongo, J.V.; Offouga Mbouoronde, C.; Nkoghe, D.; Touré, F.; Bouyou-Akotet, M.K. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Malaria, Filariasis, and Intestinal Parasites as Single Infections or Co-Infections in Different Settlements of Gabon, Central Africa. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2018, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stensvold, C.R. Laboratory Diagnosis of Blastocystis spp. Trop. Parasitol. 2015, 5, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.S.W. New Insights on Classification, Identification, and Clinical Relevance of Blastocystis spp. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 21, 639–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumarasamy, V.; Kuppusamy, U.R.; Jayalakshmi, P.; Samudi, C.; Ragavan, N.D.; Kumar, S. Exacerbation of Colon Carcinogenesis by Blastocystis sp. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumarasamy, V.; Kuppusamy, U.R.; Samudi, C.; Kumar, S. Blastocystis sp. Subtype 3 Triggers Higher Proliferation of Human Colorectal Cancer Cells, HCT116. Parasitol. Res. 2013, 112, 3551–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez, J.D.; Flórez, C.; Olivera, M.; Bernal, M.C.; Giraldo, J.C. Blastocystis Subtyping and Its Association with Intestinal Parasites in Children from Different Geographical Regions of Colombia. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wawrzyniak, I.; Poirier, P.; Texier, C.; Delbac, F.; Viscogliosi, E.; Dionigia, M.; Alaoui, H.E. Blastocystis, an Unrecognized Parasite: An Overview of Pathogenesis and Diagnosis. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2013, 1, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fellani, M.A.; Stensvold, C.R.; Vidal-Lapiedra, A.; Onuoha, E.S.U.; Fagbenro-Beyioku, A.F.; Clark, C.G. Variable Geographic Distribution of Blastocystis Subtypes and Its Potential Implications. Acta Trop. 2013, 126, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipatsatitpong, D.; Rangsin, R.; Leelayoova, S.; Naaglor, T.; Mungthin, M. Incidence and Risk Factors of Blastocystis Infection in an Orphanage in Bangkok, Thailand. Parasites Vectors 2012, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulsalam, A.M.; Ithoi, I.; Al-Mekhlafi, H.M.; Ahmed, A.; Surin, J.; Mak, J.W. Drinking Water Is a Significant Predictor of Blastocystis Infection among Rural Malaysian Primary Schoolchildren. Parasitology 2012, 139, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithyamathi, K.; Chandramathi, S.; Kumar, S. Predominance of Blastocystis sp. Infection among School Children in Peninsular Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanmard, E.; Niyyati, M.; Ghasemi, E.; Mirjalali, H.; Asadzadeh Aghdaei, H.; Zali, M.R. Impacts of Human Development Index and Climate Conditions on Prevalence of Blastocystis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acta Trop. 2018, 185, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noradilah, S.A.; Lee, I.L.; Anuar, T.S.; Salleh, F.M.; Manap, S.N.A.A.; Mohtar, N.S.H.M.; Azrul, S.M.; Abdullah, W.O.; Moktar, N. Occurrence of Blastocystis sp. in Water Catchments at Malay Villages and Aboriginal Settlement during Wet and Dry Seasons in Peninsular Malaysia. PeerJ 2016, 2016, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’Bondoukwé, N.P.; Mawili-Mboumba, D.P.; Mondouo Manga, F.; Kombila, M.; Bouyou-Akotet, M.K. Prevalence of Soil-Transmitted Helminths and Intestinal Protozoa in Shanty Towns of Libreville, Gabon. Int. J. Trop. Dis. Health 2016, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengongo, J.V.K.; Ngondza, B.P.; Ditombi, B.M.; M’bondoukwé, N.P.; Ngomo, J.M.N.; Delis, A.M.; Lekounga, P.B.; Bouyou-Akotet, M.; Mawili-Mboumba, D.P. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Intestinal Parasite Infection by HIV Infection Status among Asymptomatic Adults in Rural Gabon. Afr. Health Sci. 2020, 20, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutongo Mouandza, R.; M’Bondoukwé, N.P.; Obiang Ndong, G.P.; Nzaou Nziengui, A.; Batchy Ognagosso, F.B.; Nziengui Tirogo, C.; Moutombi Ditombi, B.; Mawili-Mboumba, D.P.; Bouyou-Akotet, M.K. Anaemia in Asymptomatic Parasite Carriers Living in Urban, Rural and Peri-Urban Settings of Gabon. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.S.; Guo, Y.L.; Shin, J.W. Hematological Effects of Blastocystis Hominis Infection in Male Foreign Workers in Taiwan. Parasitol. Res. 2003, 90, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeb, H.K.E.; Salah-Eldin, H.; Khodeer, S. Blastocystis Hominis as a Contributing Risk Factor for Development of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Pregnant Women. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 110, 2167–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Deeb, H.K.; Khodeer, S. Blastocystis spp.: Frequency and Subtype Distribution in Iron Deficiency Anemic Versus Non-Anemic Subjects from Egypt. J. Parasitol. 2013, 99, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyou-Akotet, M.K.; Mawili-Mboumba, D.P.; Kendjo, E.; Mbadinga, F.; Obiang-Bekale, N.; Mouidi, P.; Kombila, M. Anaemia and Severe Malarial Anaemia Burden in Febrile Gabonese Children: A Nine-Year Health Facility Based Survey. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 2013, 7, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyou-Akotet, M.K.; Offouga, C.L.; Mawili-Mboumba, D.P.; Essola, L.; Madoungou, B.; Kombila, M. Falciparum Malaria as an Emerging Cause of Fever in Adults Living in Gabon, Central Africa. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouyou-Akotet, M.K.; Mawili-Mboumba, D.P.; Kendjo, E.; Moutandou Chiesa, S.; Tshibola Mbuyi, M.L.; Tsoumbou-Bakana, G.; Zong, J.; Ambounda, N.; Kombila, M. Decrease of Microscopic Plasmodium Falciparum Infection Prevalence during Pregnancy Following IPTp-SP Implementation in Urban Cities of Gabon. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’Bondoukwé, N.P.; Moutongo, R.; Gbédandé, K.; Ndong Ngomo, J.M.; Hountohotegbé, T.; Adamou, R.; Koumba Lengongo, J.V.; Pambou Bello, K.; Mawili-Mboumba, D.P.; Luty, A.J.F.; et al. Circulating IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-Alpha and IL-10/IL-6 and IL-10/TNF-Alpha Ratio Profiles of Polyparasitized Individuals in Rural and Urban Areas of Gabon. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planche, T.; Krishna, S.; Kombila, M.; Engel, K.; Faucher, J.F.; Kremsner, P.G. Comparison of Methods for the Rapid Laboratory Assessment of Children with Malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2001, 65, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snounou, G.; Singh, B. Nested PCR Analysis of Plasmodium Parasites. Methods Mol. Med. 2002, 72, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Safadi, D.; Gaayeb, L.; Meloni, D.; Cian, A.; Poirier, P.; Wawrzyniak, I.; Delbac, F.; Dabboussi, F.; Delhaes, L.; Seck, M.; et al. Children of Senegal River Basin Show the Highest Prevalence of Blastocystis sp. Ever Observed Worldwide. Ever Observed Worldwide. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alfonso, R.; Santoro, M.; Essi, D.; Monsia, A.; Kaboré, Y.; Glé, C.; Di Cave, D.; Sorge, R.P.; Di Cristanziano, V.; Berrilli, F. Blastocystis in Côte d’Ivoire: Molecular Identification and Epidemiological Data. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 2243–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, C.S.; Efunshile, A.M.; Nelson, J.A.; Stensvold, C.R. Epidemiological Aspects of Blastocystis Colonization in Children in Ilero, Nigeria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 95, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokmer, A.; Cian, A.; Froment, A.; Gantois, N.; Viscogliosi, E.; Chabé, M.; Ségurel, L. Use of Shotgun Metagenomics for the Identification of Protozoa in the Gut Microbiota of Healthy Individuals from Worldwide Populations with Various Industrialization Levels. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyer, A.; Karasartova, D.; Ruh, E.; Güreser, A.S.; Turgal, E.; Imir, T.; Taylan-Ozkan, A. Epidemiology and Prevalence of Blastocystis spp. in North Cyprus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 96, 1164–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.O.; Bonde, I.; Nielsen, H.B.; Stensvold, C.R. A Retrospective Metagenomics Approach to Studying Blastocystis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. Adv. 2015, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Roka, M.; Goñi, P.; Rubio, E.; Clavel, A. Intestinal Parasites in HIV-Seropositive Patients in the Continental Region of Equatorial Guinea: Its Relation with Socio-Demographic, Health and Immune Systems Factors. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013, 107, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristanziano, V. Di; D’Alfonso, R.; Berrilli, F.; Sarfo, F.S.; Santoro, M.; Fabeni, L.; Knops, E.; Heger, E.; Kaiser, R.; Dompreh, A.; et al. Lower Prevalence of Blastocystis sp. Infections in HIV Positive Compared to HIV Negative Adults in Ghana. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyhan, Y.E.; Yilmaz, H.; Cengiz, Z.T.; Ekici, A. Clinical Significance and Prevalence of Blastocystis Hominis in Van, Turkey. Saudi Med. J. 2015, 36, 1118–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoshnood, S.; Rafiei, A.; Saki, J.; Alizadeh, K. Prevalence and Genotype Characterization of Blastocystis Hominis among the Baghmalek People in Southwestern Iran in 2013–2014. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2015, 8, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Sánchez, R.S.; Ascuña-Durand, K.; Ballón-Echegaray, J.; Vásquez-Huerta, V.; Martínez-Barrios, E.; Castillo-Neyra, R. Socio-Demographic Determinants Associated with Blastocystis Infection in Arequipa, Peru. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 104, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Safadi, D.; Cian, A.; Nourrisson, C.; Pereira, B.; Morelle, C.; Bastien, P.; Bellanger, A.P.; Botterel, F.; Candolfi, E.; Desoubeaux, G.; et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors for Infection and Subtype Distribution of the Intestinal Parasite Blastocystis sp. from a Large-Scale Multi-Center Study in France. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocaña-Losada, C.; Cuenca-Gómez, J.A.; Cabezas-Fernández, M.T.; Vázquez-Villegas, J.; Soriano-Pérez, M.J.; Cabeza-Barrera, I.; Salas-Coronas, J. Clinical and Epidemiological Characteristics of Intestinal Parasite Infection by Blastocystis hominis. Rev. Clínica Española (Engl. Ed.) 2018, 218, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leder, K.; Hellard, M.E.; Sinclair, M.I.; Fairley, C.K.; Wolfe, R. No Correlation between Clinical Symptoms and Blastocystis hominis in Immunocompetent Individuals. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005, 20, 1390–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ning, C.; Zhou, Y.; Teng, X.; Wu, X.; Chu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Chen, J.; Tian, L.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Blastocystis sp. Infections among General Populations in Yunnan Province, Southwestern China. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1791–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaherizadeh, H.; Khademvatan, S.; Soltani, S.; Torabizadeh, M.; Yousefi, E. Distribution of Haematological Indices among Subjects with Blastocystis hominis Infection Compared to Controls. Prz. Gastroenterol. 2014, 9, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavasoglu, I.; Kadikoylu, G.; Uysal, H.; Ertug, S.; Bolaman, Z. Is Blastocystis hominis a New Etiologic Factor or a Coincidence in Iron Deficiency Anemia? Eur. J. Haematol. 2008, 81, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, R.S.; Awad, S.I.; El-Baz, H.A.; Atia, G.; Kizilbash, N.A. Enteric Parasites Can Disturb Leptin and Adiponectin Levels in Children. Arch. Med. Sci. 2018, 14, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2023 Copyright by Authors. Licensed as an open access article using a CC BY 4.0 license.