Afr. J. Parasitol. Mycol. Entomol. , 2(1), 9; doi:10.35995/ajpme02010009

Pilot and Feasibility Study: Morphological, Molecular, and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) Identification of Mosquitoes and Ticks and Associated Bacteria from Côte d’Ivoire

1

Institut Pasteur of Côte d’Ivoire, Abidjan 01 BP 490, Côte d’Ivoire

2

Aix Marseille Univ, SSA, RITMES, 13005 Marseille, France

3

IHU-Méditerranée Infection, 19-21 Boulevard Jean Moulin, 13005 Marseille, France

4

IRD, MINES, Maladies Infectieuses, négligées et Emergentes au Sud, 13005 Marseille, France

*

Corresponding author: adamazandiarra@gmail.com; Tel.: +33-(0)-4-13-73-24-01; Fax: +33-(0)-4-13-73-24-02

How to Cite: Edwige, A.; Ngnindji-Youdje, Y.; Diaha-Kouamé, C.A.; Konan, K.L.; Cissé, S.; Parola, P.; Diarra, A.Z. Pilot and Feasibility Study: Morphological, Molecular, and MALDI-TOF MS Identification of Mosquitoes and Ticks and Associated Bacteria from Côte d’Ivoire. Afr. J. Parasitol. Mycol. Entomol., 2024, 2(1): 9; doi:10.35995/ajpme02010009.

Received: 22 April 2024 / Accepted: 8 April 2024 / Published: 16 August 2024

Abstract

:Introduction: Mosquitoes and ticks are arthropods and are considered to be the main vectors of human and animal diseases worldwide. The aim of this study was to use of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) to identify ticks and mosquitoes in Côte d’Ivoire. Methods: Ticks were collected from sheep reared at the Institut Pasteur and mosquitoes from the institute’s courtyard. Specimens were then identified using morphological and molecular techniques, before MALDI- TOF MS identification was attempted, by testing the obtained spectra against those from an in-house MS arthropod spectra database. Tick-associated bacteria were also identified using molecular tools. Results: A total of 16 and 47 mosquito and tick specimens were used, respectively. Morphologically, mosquitoes were only identified as the Culex genus and ticks were identified as Amblyomma variegatum (n = 36; 76.60%) and Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus (n = 11; 23.43%) species. MALDI-TOF MS combined with molecular biology showed that 14 of the mosquitoes were Culex quinquefasciatus and the 36 tick specimens were confirmed to be A. variegatum and 9 were R. (B.) microplus. Tick screening showed the presence of DNA of Rickettsia africae in A. variegatum, and of Ehrlichia canis and Ehrlichia ruminantium in R. (B.) microplus. Conclusion: MALDI-TOF MS is a fast and efficient tool for identifying arthropods. The transfer of MALDI-TOF MS technology and staff training should be encouraged in African countries for use in medical entomology and microbiology. The detection of pathogen DNA in ticks is evidence of the existence and circulation of tick-borne diseases in humans and animals.

Keywords:

mosquitoes; ticks; MALDI-TOF MS; Rickettsia sp.; Ehrlichia sp.; Côte d’Ivoire1. Introduction

Mosquitoes and ticks are hematophagous arthropods which are considered to be of major importance to human and animal public health. These arthropods are currently considered to be the two main vectors of human and animal diseases worldwide [1,2,3]. Mosquitoes belong to the Culicidae family, comprising some 3563 species and subspecies subdivided into 44 genera. Among the mosquito genera, Anopheles spp., Aedes spp., and Culex spp. are the most important vectors, due to their role in the transmission of various pathogens, including parasites, viruses, and bacteria [4]. Ticks are divided into three families: Argasidae (soft ticks), Ixodidae (hard ticks), and Nuttalliellidae, with around 900 recognised species [5]. Around ten percent of known tick species can transmit a wide variety of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, protozoa, and helminths [6].

The accurate identification of arthropods and the detection of associated micro-organisms are crucial steps in characterising and mapping competent vectors [7]. The gold standard technique for identifying arthropods is morphological identification, based mainly on the observation of morphological features [8]. Morphological identification is, however, limited by a lack of experts capable of identifying arthropods, a lack available dichotomous keys for developmental stages, and the impossibility of identifying species complexes or damaged or gorged specimens for ticks [7]. The limitations of morphological identification can be overcome using molecular biological techniques. However, this identification technique is time-consuming, laborious, and costly, preventing its widespread use [9]. From the 2010s to the present day, several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of MALDI-TOF MS at identifying numerous arthropod species. Today, MALDI-TOF MS is presented as an alternative or complementary method to morphological and molecular identification for arthropods [9]. MALDI-TOF MS is a simple, rapid technique, with no need for entomological expertise, and less expensive reagents, despite the initial high cost of the machine and its maintenance [9].

This study was carried out as part of a partnership aimed at training a visitor in the use of innovative techniques applied to arthropod identification and to transfer the techniques to Côte d’Ivoire to perform on-site studies on a large number of specimens.

Our aim was to integrate morphological, proteomic (MALDI-TOF MS), and molecular methods to identify ticks and mosquitoes, and to search for tick-associated micro-organisms using molecular biological tools.

2. Methods

2.1. Tick and Mosquito Collection Zones

Ticks were collected from sheep reared at the Institut Pasteur de Côte d’Ivoire in Adiopodoumé (36″42′ 2″ N, 8″18″50″ E) in the commune of Yopougon, and mosquitoes were collected in the institute’s courtyard. This site is located in the extreme northeast of the country and is characterised by Mediterranean climatic conditions and an altitude of 400 m. The hot season extends from May to October, with average temperatures above 20 °C, and the cold season extends from November to April, with average temperatures below 16 °C. Average annual precipitation is 556 mm, but rainfall is irregular, ranging from 23 mm in summer to 221 mm in winter.

2.2. Collection and Morphological Identification of Mosquitoes and Ticks

Mosquitoes were collected using a mouth aspirator on site between March and April 2022. Mosquitoes were counted, identified to the genus level, and stored in dry tubes at room temperature. Ticks were collected from sheep reared at the Institut Pasteur in March 2022. Ticks were identified with a binocular magnifying glass using identification keys [8], then stored in tubes containing 70% ethanol for one to two months before MALDI-TOF MS analysis. Mosquitoes and ticks were transferred to the IHU Mediterranean infection laboratory (Marseille, France) for analysis. In Marseille, the morphological identification of tick specimens was verified by two tick specialists using a magnifying glass (Zeiss Axio Zoom.V16,Zeiss, Marly le Roi, France) using the key developed by Walker et al. [8]. The number of rows of teeth in the subgenus Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) column was observed using an electron microscope (SEM Hitachi TM4000 Plus) and photographed for species identification.

2.3. Mosquito and Tick Dissection

Mosquitoes were dissected individually using a sterile surgical blade under a binocular magnifying glass. For each specimen, the legs and thorax (without wings) were harvested and transferred separately into 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes for MALDI-TOF MS analysis, and the other body parts (abdomens and heads) were transferred into another 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube used for any molecular analysis [10].

The four legs on the same side of each tick were cut off using a sterile surgical blade, and the tick body was cut longitudinally into two halves. All four legs were used for MALDI-TOF MS analysis, the half of the tick without legs was selected for molecular analysis, and the second half with the remaining legs was stored at −20 °C [11].

2.4. Sample Homogenisation and MALDI-TOF MS Analysis

Each dissected mosquito and tick compartment were individually homogenised using a TissueLyser (Qiagen) and glass powder (Sigma-Aldrich, Lyon, France) in a homogenisation buffer composed of a mixture of 70% formic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Lyon, France) and 50% acetonitrile (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland), as previously described [10,11]. After homogenisation of the sample, rapid centrifugation was performed and 1 μL of the supernatant from each sample was deposited on the MALDI-TOF steel target plate in quadruplicate (Bruker Daltonics, Wissembourg, France). After drying at room temperature, 1 μL of the matrix solution composed of saturated α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Lyon, France), 50% (v/v) acetonitrile, 2.5% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK), and HPLC-grade water was added. To check the quality of the matrix and the performance of the MALDI-TOF device, A. variegatum bred in our laboratory were included on each plate and used as positive controls.

2.5. MALDI-TOF MS Parameters

Protein mass profiles were obtained using a Microflex LT MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany), with detection in the linear positive-ion mode at a laser frequency of 50 Hz within a mass range of 2–20 kDa. The setting parameters of the MALDI-TOF MS apparatus were identical to those previously used [12]. The spectrum profiles obtained were visualised with flexAnalysis v.3.3 software and exported to ClinProTools version v.2.2 and MALDI-Biotyper v.3.0 (Bruker Daltonics, Germany) for data processing (smoothing, baseline subtraction, peak picking) and evaluation with cluster analysis.

2.6. MS Spectral Analysis and Blind Test

MS spectral profiles were visualised with flexAnalysis v.3.3 software (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). The reproducibility of the MS spectra was assessed by comparing the mean spectral profiles (main spectrum profile, MSP) obtained from the four spots for each specimen with MALDI-Biotyper v.3.0 software (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) [10]. Cluster analyses (MS dendrogram) were performed on the basis of MSP comparisons given by MALDI-Biotyper v.3.0 software [10].

MS spectra of mosquito legs and thorax, and tick legs were tested against reference MS spectra from the in-house arthropod spectra database containing spectra of several mosquito and tick species (Supplementary Table S1) [13]. The reliability of species identification was estimated using log-score values (LSV) obtained from MALDI-Biotyper v.3.0 software, ranging from 0 to 3. LSV ≥ 1.7 was considered reliable for species identification [14,15].

2.7. DNA Extraction and Molecular Identification of Mosquitoes and Ticks

To confirm the morphological and MALDI-TOF MS identification, six mosquito and eight tick specimens were selected and submitted for molecular analysis. Of these, 4/6 mosquitoes had been identified via MALDI-TOF MS as C. quinquefasciatus with an LSV ≥ 1.7, which was considered a reliable identification [14]. For the remaining 2/6 mosquitoes, an LSV < 1.7 was obtained. The eight tick specimens tested using molecular tools were four A. variegatum and four R. (B.) microplus identified through MALDI-TOF MS with LSVs > 1.7.

Genomic DNA was extracted from the abdomen and head of these mosquitoes and from the legless half of these ticks using the EZ1 DNA Tissue Kit (Qiagen), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Mosquitoes and ticks were identified via standard PCR using the cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene amplifying approximately 720 bp [4] and the 16S tick gene amplifying 400 bp [16]. The amplified products were purified and sequenced as described previously [17]. The obtained sequences were assembled and corrected using Chromas Pro1.77 (Technelysium Pty. Ltd., Tewantin, Australia) and a BLAST query was performed against the NCBI GenBank database [18] and COI sequences of mosquitoes against the Barcode of Life Data Systems database (BOLD) [19].

2.8. Molecular Detection of Micro-Organisms in Ticks

Tick and mosquito specimens were qPCR-tested for the presence of Rickettsia spp., Bartonella spp., Anaplasmataceae, Borrelia spp., Coxiella burnetii, and Piroplasmida using primers and probes, as previously described [20,21]. qPCR was performed using the CFX96 real-time system (Bio-Rad, Marnes-La-Coquette, France). The qPCR reaction contained DNA from Rickettsia montanensis, Bartonella elizabethae, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Coxiella burnetii, Borrelia crocidurae, and Babesia vogeli from our laboratory cultures as a positive control and DNA from R. sanguineus s.l reared in our laboratory, which are known to be free of the bacteria cited above, as a negative control. The samples were considered to be positive when the cycle threshold (Ct) was less than 36 [21].

Positive samples for Rickettsia spp. were then submitted to a qPCR system specifically for detecting R. africae [21]. Samples positive for Anaplasmataceae spp. were subjected to standard PCR and sequencing by the amplification of a 520 bp fragment of the 23S rRNA gene to identify bacterial species [21]. The Anaplasmataceae spp. sequences obtained were assembled and analysed with ChromasPro software (Version 1.7.7) (Technelysium Pty. Ltd., Tewantin, QL, Australia), and then compared with the NCBI reference sequence database, which is available in GenBank (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) [18].

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Identification

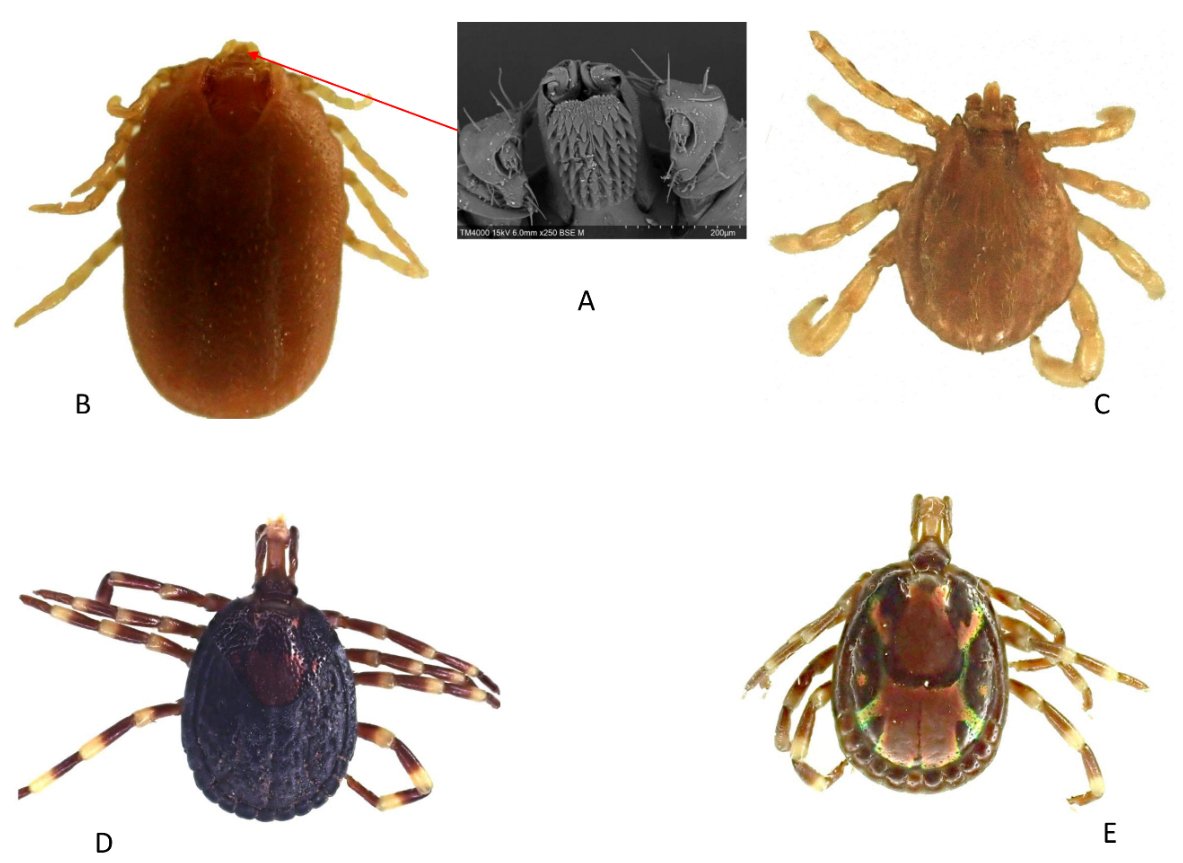

A total of 16 mosquito specimens and 47 tick specimens were collected. Morphologically, mosquitoes were all identified as Culex spp. Ticks were identified morphologically as A. variegatum (n = 36; 76.60%) and R. (B.) microplus (n = 11; 23.43%). The number of rows of hypostomal teeth that we observed under the electron microscope in Rhipicephalus spp. was 4+4 columns, hence the identification of these ticks as R. (B.) microplus (Figure 1A). Photos of female and male R. (B.) microplus (Figure 1B,C) and female and male A. variegatum (Figure 1D,E) are presented below.

Figure 1.

Electron microscope image of the number of hypostomal rows of teeth of R. (B.) microplus (A). Dorsal view of R. (B.) microplus female (B), male (C) and A. variegatum female (D), male (E).

Figure 1.

Electron microscope image of the number of hypostomal rows of teeth of R. (B.) microplus (A). Dorsal view of R. (B.) microplus female (B), male (C) and A. variegatum female (D), male (E).

3.2. Identification of Mosquitoes and Ticks via MALDI-TOF MS

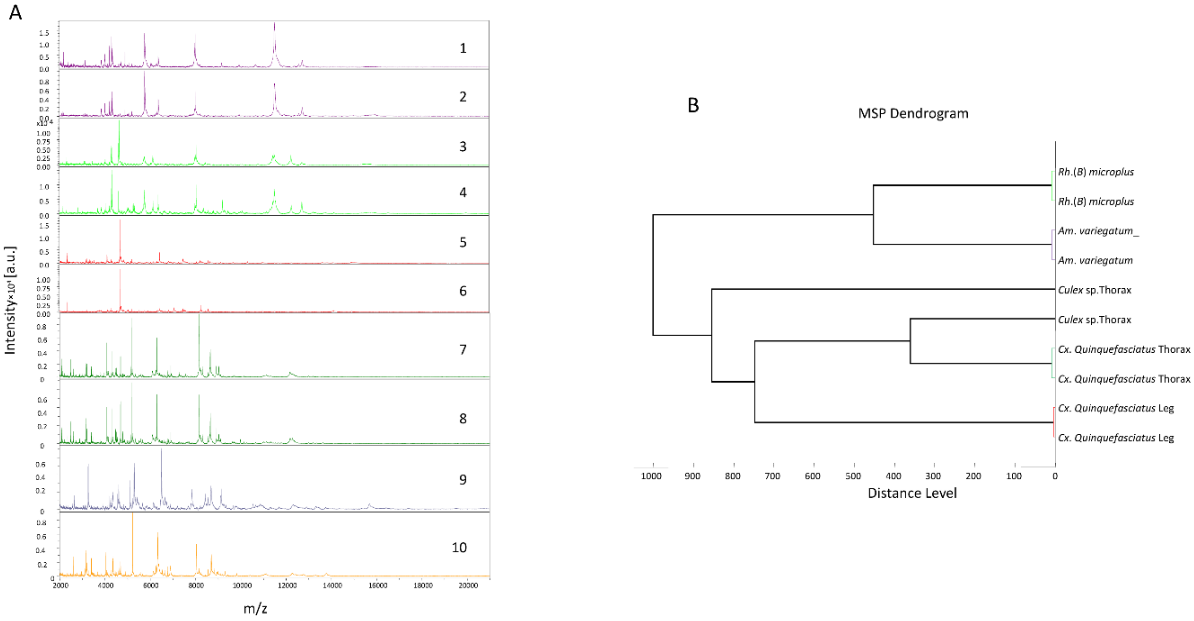

Analysis of the MS spectra profiles of tick legs showed that 100% (36/36) and 81.81% (9/11) were of high intensity (>3000 arbitrary unit (a.u.)) and quality, respectively, for A. variegatum and R. (B.) microplus (Table 1). Similarly for mosquitoes, 100% (16/16) of thorax spectra and 93.75% (15/16) of leg spectra were of high intensity (>3000 a.u.) and quality (Table 1). A visual comparison of the MS profiles of mosquito and tick legs and thoraxes shows that they differed considerably (Figure 2A). Cluster analyses of MS spectra from mosquito legs and thoraxes, and tick legs, showed that specimens of the same species were grouped together (Figure 2B). Tick and mosquito spectra used for visual comparison and cluster analysis are available at the following link: https://doi.org/10.35081/17tx-qm42.

Figure 2.

Specific MALDI-TOF MS spectra of mosquitoes and ticks species. (A) Representation of leg MS spectra from A. variegatum (1, 2), R. (B.) microplus (3, 4), C. quinquefasciatus (5, 6), thorax of C. quinquefasciatus (7, 8), and the thorax of Culex sp. (9, 10). (B) Dendrogram constructed using one to two representative MS spectra from mosquito and tick species.

Figure 2.

Specific MALDI-TOF MS spectra of mosquitoes and ticks species. (A) Representation of leg MS spectra from A. variegatum (1, 2), R. (B.) microplus (3, 4), C. quinquefasciatus (5, 6), thorax of C. quinquefasciatus (7, 8), and the thorax of Culex sp. (9, 10). (B) Dendrogram constructed using one to two representative MS spectra from mosquito and tick species.

Table 1.

The number of mosquito and tick species used for MALDI-TOF MS analysis and identification percentages.

Table 1.

The number of mosquito and tick species used for MALDI-TOF MS analysis and identification percentages.

| Arthropods Species | Number of Specimens Tested | Good-Quality Spectra (%) | MALDI-TOF MS Identification (n) | LSVs Range (Average ± Standard Deviation) | Number with LSVs ≥ 17 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culex spp. | 16 | 15L (93.75%) | C. quinquefasciatus (n = 14) | 1.915 to 2.505 (2.250 ± 0.206) | 14 (100%) |

| Unidentified (n = 1) | 1.345 | / | |||

| 16T (100%) | C. quinquefasciatus (n = 14) | 1.887 to 2.405 (2.159 ± 0.185) | 14 (100%) | ||

| Unidentified (n = 2) | 1.315 and 1.687 | / | |||

| A. variegatum | 36 | 36 (100%) | A. variegatum (n = 36) | 1.811 to 2.211 (1.975 ± 0.081) | 36 (100%) |

| R. (B.) microplus | 11 | 9 (81.81%) | R. (B.) microplus (n = 9) | 1.753 to 2.068 (1.924 ± 0.094) | 9 (100%) |

L = Legs, T = thoraxes.

Quality MS spectra with intensity (>3000 a.u.), i.e., mosquito legs (n = 15) and thorax (n = 16), and tick legs (n = 47) were compared to our in-house database of MALDI-TOF MS arthropod spectra. Identification scores (LSVs) ranged from 1.315 to 2.505 with a mean of 2.056 ± 0.185 for mosquito legs and from 1.224 to 2.405 (mean = 2.156 ± 0.206) for mosquito thoraxes. The LSVs ranged from 1.811 to 2.211 (mean = 1.975 ± 0.081) and from 1.753 to 2.068 (mean = 1.924 ± 0.094) for A. variegatum and R. (B.) microplus legs, respectively (Table 1). The leg spectra of 14/15 mosquitoes were identified as those of C. quinquefasciatus, of which 100% had LSVs ≥ 1.7. Also, 1/15 spectrum was unidentified (LSV < 1.7) (Table 1). For mosquito thorax spectra, 14/16 were identified as C. quinquefasciatus, of which all (14/14) had LSV ≥ 1.7, and 2/16 spectra were unidentified. For ticks, 100% (36/36) of the leg spectra of A. variegatum and 100% (9/9) of R.(B.) microplus were identified through MALDI-TOF MS as A. variegatum and R.(B.) microplus with LSV ≥ 1.7 (Table 1).

3.3. Molecular Identification of Mosquitoes and Ticks

Four specimens identified via MALDI-TOF MS as C. quinquefasciatus specimens and eight tick specimens (four A. variegatum and four R. (B.) microplus identified via morphology and MS) were submitted to molecular identification for confirmation. Similarly, the two specimens that had been considered Culex sp. on the basis of their morphology, but whose leg and/or thorax spectra had not been identified through MALDI-TOF MS were also subjected to molecular identification in order to determine the species.

A comparison of the four specimen sequences identified via MALDI-TOF MS as C. quinquefasciatus with LSV > 1.7 with sequences from the NCBI GenBank and BOLD databases showed that they were 100% identical to the sequence of C. quinquefasciatus (MK575480) contained in both databases. For the two specimens which were not identified via MALDI-TOF MS, the sequence of one of the specimens was 92.26% identical to the sequence of Coquillettidia maculipennis (GQ165785) available in the NCBI GenBank and BOLD. The sequence of the other specimen was 99.69% identical to that which was deposited as an unidentified specimen of Chironomidae (MZ634079), available in NCBI GenBank and BOLD. The sequences of Am. variegatum and R. (B.) microplus were 100% identical to the sequences of A. variegatum (JF949794) and R. (B.) microplus (EU918187).

3.4. Molecular Detection of Micro-Organisms in Ticks

The screening of DNA extracted from ticks revealed the presence of DNA of Rickettsia spp. in 26/36 (72.22%) of A. variegatum and of bacteria of the Anaplasmataceae family in 7/11 (63.63%) of R. (B.) microplus. DNA of the other micro-organisms tested (Bartonella spp., Borrelia spp., Coxiella burnetii and Piroplasmida) was not found in our ticks. All mosquito specimens were negatives for Rickettsia spp., Bartonella spp., Anaplasmataceae, Borrelia spp., Coxiella burnetii, and Piroplasmida. All ticks positive for Rickettsia spp. were identified as R. africae through specific qPCR. Sequencing of seven specimens positive for bacteria of the Anaplasmataceae family yielded five sequences. The BLAST of these sequences against the NCBI GenBank database showed that four sequences were 98.54% identical with the Ehrlichia canis sequence (KY498333) and one was 100% identical with Ehrlichia ruminantium (CR925677).

4. Discussion

In this study, which focused on mosquitoes and ticks, MALDI-TOF MS confirmed the morphological identification of ticks and enabled us to identify all mosquitoes except two specimens which we considered to be mosquitoes, and which were in fact other insects. The limitations of our study could be the small number of specimens and the difference between the number of mosquito and tick specimens. However, the study was conducted to train a visitor in MALDI-TOF MS techniques, whose effectiveness in the identification of on hundreds or thousands of mosquito and tick specimens has been proven [11,13,14,21]. In terms of micro-organisms, the presence of DNA from R. africae, E. canis, and E. ruminantium was found in ticks.

MALDI-TOF MS is a technique for identifying protein macromolecules through sample ionisation. The sample to be analysed is coated with a matrix, then struck by a laser beam which induces the desorption and ionisation of the sample. The ions are generated separately from each other on the basis of a mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) [9]. Measurement of this ratio is determined by the time-of-flight required for an ion to pass through the tube to the detector (time-of-flight). This process generates a spectrum that reveals information about the protein composition of the sample analysed, and may enable its identification [9].

The MALDI-TOF MS technique has been used in microbiology since the early 2000s to identify bacteria, fungi, and yeasts. Recently, the technique has been successfully applied to identify protozoa, intestinal helminths, and several arthropod species [9]. The speed, cost-effectiveness, and reliability of this approach have largely contributed to its use in clinical microbiology laboratories for routine diagnosis worldwide. The principle involves comparing MS spectra of unknown microbial organisms with a database containing reference MS spectra of thousands of microbial species [9].

This study highlights the usefulness of MALDI-TOF MS in identifying arthropods, particularly for mosquito specimens that could not be identified morphologically. However, two insect specimens could not be identified either by MALDI-TOF MS or by molecular biology, demonstrating that morphological identification is an essential step in the constitution of molecular and proteomic databases. This shows that the different identification methods, despite the limitations and advantages of each, are complementary and should be used in an integrative way [16].

In this study, all the mosquitoes had only been identified morphologically to the genus level (Culex sp.) due to the lack of experts able to differentiate the Culex species, and also because the specimens were damaged, which made the typically distinguishable characteristics poorly visible. This explains the interest researchers have toward MALDI-TOF MS, which requires no particular expertise in entomology [9]. The MALDI-TOF MS tool enabled us to identify all the mosquitoes at the species level, with the exception of two specimens.

Most of the mosquitoes had been identified by MALDI-TOF MS as C. quinquefasciatus. The MS profiles of the legs and thorax of Culex specimens are different, as shown in the dendrogram. This difference is linked to the different protein composition of Culex legs and thoraxes. Previous studies had already shown a difference between the MS profiles of different body parts of the same arthropod [16,22,23,24]. This identification was confirmed by molecular biology using randomly selected specimens. Culex quinquefasciatus is a mosquito which is widespread in tropical urban areas. It feeds on the blood of humans and animals, and this behaviour enables it to play an important role in the amplification and transmission of zoonotic diseases [25]. This mosquito is responsible for the transmission of a wide variety of pathogens, including Wuchereria bancrofti (which is responsible for lymphatic filariasis), the parasite of avian malaria (Plasmodium relictum), West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis, St. Louis fever, and Rift Valley fever [25]. In addition to their role as vectors, C. quinquefasciatus also cause serious harm to humans by biting them while they are taking their blood meals [25]. In Côte d’Ivoire, C. quinquefasciatus has been reported in several localities, representing the most abundant mosquito species [26,27].

Interestingly, the COI gene sequences of two specimens thought to be Culex sp. were closer to the sequences of C. maculipennis and an insect of the Chironomidae family, according to the molecular results. However, given the percent identity of these sequences, the two specimens are undoubtedly other insects whose species have not yet been identified. Ultimately, these two specimens were not identified at the species level by either MALDI-TOF MS or molecular biology.

Chironomids (Diptera: Chironomidae), known as “non-biting midges”, are the most numerous family of freshwater insects [28]. The Chironomidae are mosquito-like insects, but lack the wing scales and elongated mouthparts of the Culicidae; they are distributed worldwide and divided into eleven subfamilies. More than 5000 species have been described [28]. The genus Coquillettidia (Culicidae, Diptera) are mosquitoes considered natural vectors of avian malaria in Africa, and adults of Coquillettidia spp. are easily confused with Aedes and Culex [29].

Two tick species were identified in our study: A. variegatum and R. (B.) microplus. In ticks, R. (B.) microplus 4+4 columns of hypostomal teeth [8], which is one of the discriminating criteria, could be clearly observed. The tick A. variegatum is widely distributed in sub-Saharan Africa, causing substantial economic losses in domestic ruminants through exsanguination or physical injury, and also through the transmission of Ehrlichia ruminantium, the agent of cowdriosis (“heartwater”) [30]. This tick is also the main vector of R. africae, the agent of African tick bite fever (ATBF) in sub-Saharan Africa [31]. The Amblyomma variegatum tick has been found in several studies in Côte d’Ivoire [31,32,33,34] and used to represent the most predominant species on cattle before the discovery of R. (B.) microplus in 2007 [35]. Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus is a Southeast Asian tick, introduced into West Africa probably through the uncontrolled importation of live cattle from Brazil [36]. This exotic tick was first discovered in Côte d’Ivoire in 2007 [37] after its introduction, and has since gradually spread to other West African countries [35]. This tick is an effective vector of Babesia bovis, Babesia bigemina, and Anaplasma marginale, the pathogens of babesiosis, and anaplasmosis, respectively, in cattle [35,38].

With regard to tick-borne micro-organisms, we found the DNA of R. africae in A. variegatum, the DNA of E. ruminantium, and a bacterium close to E. canis in R. (B.) microplus.

ATBF is a rickettsial disease caused by R. africae, an obligate intracellular Gram-negative bacterium transmitted by ticks of the genus Amblyomma, mainly A. variegatum in sub-Saharan Africa [39]. Although ATBF is an acute febrile illness, it is often undiagnosed or misdiagnosed in Africa due to the lack of effective laboratory diagnostic tools, but also because the disease is most often benign, and eschars and mild rashes are more difficult to detect in black-skinned people [39,40,41]. However, after malaria, ATBF is the most frequently documented fever aetiology in travellers returning from sub-Saharan Africa [41].

In Côte d’Ivoire, DNA of R. africae has already been reported in several tick species [31,42], as well as in ticks from several African countries [39]. Ehrlichia ruminantium, the causative agent of cowdriosis in wild and domestic ruminants, is transmitted mainly by ticks of the genus Amblyomma [43]. The disease is present in most of sub-Saharan Africa, with the exception of the very dry southwest [43]. In Côte d’Ivoire, E. ruminantium DNA was detected in A. variegatum, the main vector [31], and R. (B.) microplus. In other West African countries, notably Benin, Burkina Faso, Gambia, Nigeria, and Mali, E. ruminantium DNA has been detected in Am. variegatum and several tick species, including R. (B.) microplus [21,44,45,46,47]. Ehrlichia canis is an obligate intracellular bacterium that causes canine monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (CME) in dogs, mainly transmitted by Rhipicephalus sanguineus, the brown dog tick [48]. The presence of E. canis DNA and antibodies against E. canis have been reported in R. sanguineus ticks and dog blood, respectively, in previous studies in Côte d’Ivoire [49,50,51]. In this study, E. canis DNA was detected in R. (B.) microplus, which is not the main vector of this bacterium. However, the presence of Ehrlichia DNA, close to E. canis, in R. (B.) microplus has been reported in some studies [52,53].

5. Conclusion

This study shows that MALDI-TOF MS is a powerful tool for arthropod identification. Although this tool is currently more widely used in developed countries, it remains little used, if at all, in developing countries, particularly in Africa. This study enabled us to train personnel in the use of the MALDI-TOF MS technique and to transfer the MALDI-TOF MS technology. The use of MALDI-TOF MS in future entomology studies on a large number of specimens in Côte d’Ivoire will improve and facilitate the identification of infectious disease vectors such as mosquitoes and ticks. Limitations to the use of this technique include the development of the protocol (choice of compartment, sample grinding time), sample storage conditions, the construction of a reliable database with the spectra of specimens formally identified morphologically and/or molecularly, and the cost of the device. However, the device can be used on bacteriology, mycology, and entomology platforms [9]. We believe that the MALDI-TOF MS tool could be of substantial benefit of medical interest in terms of cost or added value for the diagnosis of arthropods such as ticks and mosquitoes, despite the fact that resources are limited in Africa.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://ajpme.jams.pub/article/conversion/supplementary/f0b00c5ed691e3cf566df6bc7b02d5e2, Table S1: Lists of arthropod species contained in our MALDI-TOF MS database, modes of consevation and compartment used for MALDI-TOF MS analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: A.E., C.A.D.-K., S.C. and P.P.; Formal analysis: A.E., Y.N.-Y. and A.Z.D.; Investigation: A.E.; Methodology: A.E., Y.N.-Y., P.P. and A.Z.D.; Project administration: P.P.; Resources: P.P.; Supervision: A.Z.D. and P.P.; Validation: A.E., A.Z.D., and P.P.; Writing—original draft preparation: A.E. and A.Z.D.; Writing—review and editing: A.E., Y.N.-Y., A.Z.D. and P.P.; C.A.D.-K. provided the ticks for this study; K.L.K. provided the mosquitoes for this study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire (IHU) Méditerranée Infection, the French National Research Agency under the “Investissements d’avenir” programme, reference ANR-10-IAHU-03, the Région Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur and European ERDF PRIMI funding. A.E. was supported by AMRUGE-CI (Support for the Modernization and Reform of Universities and Grandes Ecoles of Côte d’Ivoire), developed within the framework of the Debt Reduction and Development Contract (C2D).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those who participated in sample collection and the Institut Pasteur sheep breeders.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Azari-Hamidian, S.; Norouzi, B.; Harbach, R.E. A detailed review of the mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) of Iran and their medical and veterinary importance. Acta Trop. 2019, 194, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas-Torres, F.; Chomel, B.B.; Otranto, D. Ticks and tick-borne diseases: A One Health perspective. Trends Parasitol. 2012, 28, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongejan, F.; Uilenberg, G. The global importance of ticks. Parasitology 2004, 129, S3–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, L.N.; Tran, L.B.; Nguyen, H.S.; Ho, V.H.; Parola, P.; Nguyen, X.Q. Mosquitoes and Mosquito-Borne Diseases in Vietnam. Insects. 2022, 13, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, S.C.; Murrell, A. Systematics and evolution of ticks with a list of valid genus and species names. Parasitology. 2004, 129, S15–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, P. Tick-borne rickettsial diseases: Emerging risks in Europe. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2004, 27, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yssouf, A.; Almeras, L.; Raoult, D.; Parola, P. Emerging tools for identification of arthropod vectors. Future Microbiol. 2016, 11, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.R.; Bouattour, A.; Camicas, J.L.; Estrada-Peña, A.; Horak, I.G.; Latif, A.A.; Pegram, R.G.; Preston, P.M. Ticks of Domestic Animals in Africa: A Guide to Identification of Species; Bioscience Reports: Edinburgh, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sevestre, J.; Diarra, A.Z.; Laroche, M.; Almeras, L.; Parola, P. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry: An emerging tool for studying the vectors of human infectious diseases. Future Microbiol. 2021, 16, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Rua, A.; Pages, N.; Fontaine, A.; Nuccio, C.; Hery, L.; Goindin, D.; Gustave, J.; Almeras, L. Improvement of mosquito identification by MALDI-TOF MS biotyping using protein signatures from two body parts. Parasit. Vectors 2018, 11, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoy, S.; Diarra, A.Z.; Laudisoit, A.; Gembu, G.C.; Verheyen, E.; Mubenga, O.; Mbalitini, S.G.; Baelo, P.; Laroche, M.; Parola, P. Using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry to identify ticks collected on domestic and wild animals from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2021, 84, 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebbak, A.; El, H.B.; Berenger, J.M.; Bitam, I.; Raoult, D.; Almeras, L.; Parola, P. Comparative analysis of storage conditions and homogenization methods for tick and flea species for identification by MALDI-TOF MS. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2017, 31, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diarra, A.Z.; Laroche, M.; Berger, F.; Parola, P. Use of MALDI-TOF MS for the Identification of Chad Mosquitoes and the Origin of Their Blood Meal. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 100, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, L.N.; Diarra, A.Z.; Nguyen, H.S.; Tran, L.B.; Do, V.N.; Ly, T.D.A.; Ho, V.H.; Nguyen, X.Q.; Parola, P. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry identification of mosquitoes collected in Vietnam. Parasit. Vectors 2022, 15, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevestre, J.; Diarra, A.Z.; Oumarou, H.A.; Durant, J.; Delaunay, P.; Parola, P. Detection of emerging tick-borne disease agents in the Alpes-Maritimes region, southeastern France. Ticks Tick. Borne Dis. 2021, 12, 101800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, P.H.; Almeras, L.; Plantard, O.; Grillon, A.; Talagrand-Reboul, E.; McCoy, K.; Jaulhac, B.; Boulanger, N. Identification of closely related Ixodes species by protein profiling with MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumsa, B.; Laroche, M.; Almeras, L.; Mediannikov, O.; Raoult, D.; Parola, P. Morphological, molecular and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry identification of ixodid tick species collected in Oromia, Ethiopia. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 4199–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, D.A.; Cavanaugh, M.; Clark, K.; Karsch-Mizrachi, I.; Ostell, J.; Pruitt, K.D.; Sayers, E.W. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D41–D47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnasingham, S.; Hebert, P.D. bold: The Barcode of Life Data System (http://www.barcodinglife.org). Mol. Ecol. Notes 2007, 7, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmana, H.; Granjon, L.; Diagne, C.; Davoust, B.; Fenollar, F.; Mediannikov, O. Rodents as Hosts of Pathogens and Related Zoonotic Disease Risk. Pathogens 2020, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diarra, A.Z.; Almeras, L.; Laroche, M.; Berenger, J.M.; Kone, A.K.; Bocoum, Z.; Dabo, A.; Doumbo, O.; Raoult, D.; Parola, P. Molecular and MALDI-TOF identification of ticks and tick-associated bacteria in Mali. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briolant, S.; Costa, M.M.; Nguyen, C.; Dusfour, I.; Pommier, d.S.V.; Girod, R.; Almeras, L. Identification of French Guiana anopheline mosquitoes by MALDI-TOF MS profiling using protein signatures from two body parts. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.M.; Guidez, A.; Briolant, S.; Talaga, S.; Issaly, J.; Naroua, H.; Carinci, R.; Gaborit, P.; Lavergne, A.; Dusfour, I.; et al. Identification of Neotropical Culex Mosquitoes by MALDI-TOF MS Profiling. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppenheit, A.; Murugaiyan, J.; Bauer, B.; Steuber, S.; Clausen, P.H.; Roesler, U. Identification of Tsetse (Glossina spp.) using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time of flight mass spectrometry. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tia, I.Z.; Barreaux, A.M.G.; Oumbouke, W.A.; Koffi, A.A.; Ahoua Alou, L.P.; Camara, S.; Wolie, R.Z.; Sternberg, E.D.; Dahounto, A.; Yapi, G.Y.; et al. Efficacy of a ‘lethal house lure’ against Culex quinquefasciatus from Bouake city, Cote d’Ivoire. Parasit. Vectors 2023, 16, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N’Dri, B.P.; Wipf, N.C.; Saric, J.; Fodjo, B.K.; Raso, G.; Utzinger, J.; Müller, P.; Mouhamadou, C.S. Species composition and insecticide resistance in malaria vectors in Ellibou, southern Cote d’Ivoire and first finding of Anopheles arabiensis in Cote d’Ivoire. Malar. J. 2023, 22, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoly, F.N.; Zahouli, J.B.Z.; Meite, A.; Opoku, M.; Kouassi, B.L.; de Souza, D.K.; Bockarie, M.; Koudou, B.G. Low transmission of Wuchereria bancrofti in cross-border districts of Cote d’Ivoire: A great step towards lymphatic filariasis elimination in West Africa. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fard, M.S.; Pasmans, F.; Adriaensen, C.; Laing, G.D.; Janssens, G.P.; Martel, A. Chironomidae bloodworms larvae as aquatic amphibian food. Zoo Biol. 2014, 33, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njabo, K.Y.; Cornel, A.J.; Sehgal, R.N.; Loiseau, C.; Buermann, W.; Harrigan, R.J.; Pollinger, J.; Valkiūnas, G.; Smith, T.B. Coquillettidia (Culicidae, Diptera) mosquitoes are natural vectors of avian malaria in Africa. Malar. J. 2009, 8, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beati, L.; Patel, J.; Lucas-Williams, H.; Adakal, H.; Kanduma, E.G.; Tembo-Mwase, E.; Krecek, R.; Mertins, J.W.; Alfred, J.T.; Kelly, S.; et al. Phylogeography and demographic history of Amblyomma variegatum (Fabricius) (Acari: Ixodidae), the tropical bont tick. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012, 12, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehounoud, C.B.; Yao, K.P.; Dahmani, M.; Achi, Y.L.; Amanzougaghene, N.; N’douba, A.K.; N’guessan, J.D.; Raoult, D.; Fenollar, F.; Mediannikov, O. Multiple pathogens including potential new species in tick vectors in Cote d’Ivoire. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjogoua, E.V.; Coulibaly-Guindo, N.; Diaha-Kouame, C.A.; Diane, M.K.; Kouassi, R.M.C.K.; Coulibaly, J.T.; Dosso, M. Geographical distribution of ticks ixodidae in Cote d’Ivoire: Potential reservoir of the Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2021, 21, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knopf, L.; Komoin-Oka, C.; Betschart, B.; Jongejan, F.; Gottstein, B.; Zinsstag, J. Seasonal epidemiology of ticks and aspects of cowdriosis in N’Dama village cattle in the Central Guinea savannah of Cote d’Ivoire. Prev. Vet. Med. 2002, 53, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuo, Z.; Yao, K.P.; Bi, Z.F.Z.; Douan, B.G.; N’Goran, E.K. Ticks of Cattle (Bos taurus and Bos indicus) and Grasscutters (Thryonomys swinderianus) in Savannas District of Cote-d’Ivoire. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 2020, 113, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boka, O.M.; Achi, L.; Adakal, H.; Azokou, A.; Yao, P.; Yapi, Y.G.; Kone, M.; Dagnogo, K.; Kaboret, Y.Y. Review of cattle ticks (Acari, Ixodida) in Ivory Coast and geographic distribution of Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus, an emerging tick in West Africa. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2017, 71, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toure, A.; Sanogo, M.; Sghiri, A.; Sahibi, H. Incidences of Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus (Canestrini, 1888) transmitted pathogens in cattle in West Africa. Acta Parasitol. 2022, 67, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madder, M.; Thys, E.; Geysen, D.; Baudoux, C.; Horak, I. Boophilus microplus ticks found in West Africa. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2007, 43, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madder, M.; Thys, E.; Achi, L.; Toure, A.; De, D.R. Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus: A most successful invasive tick species in West-Africa. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2011, 53, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, A.; Manyangadze, T.; Mukaratirwa, S. Prevalence of Rickettsia africae in tick vectors collected from mammalian hosts in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ticks Tick. Borne Dis. 2022, 13, 101960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, N.; Kutsuna, S.; Takaya, S.; Katanami, Y.; Ohmagari, N. Imported African Tick Bite Fever in Japan: A Literature Review and Report of Three Cases. Intern. Med. 2022, 61, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diarra, A.Z.; Kelly, P.; Davoust, B.; Parola, P. Tick-Borne Diseases of Humans and Animals in West Africa. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socolovschi, C.; Huynh, T.P.; Davoust, B.; Gomez, J.; Raoult, D.; Parola, P. Transovarial and trans-stadial transmission of Rickettsiae africae in Amblyomma variegatum ticks. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2009, 15 (Suppl. 2), 317–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allsopp, B.A. Heartwater-Ehrlichia ruminantium infection. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2015, 34, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anifowose, O.I.; Takeet, M.I.; Talabi, A.O.; Otesile, E.B. Molecular detection of Ehrlichia ruminantium in engorged ablyomma variegatum and cattle in Ogun State, Nigeria. J. Parasit. Dis. 2020, 44, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biguezoton, A.; Noel, V.; Adehan, S.; Adakal, H.; Dayo, G.K.; Zoungrana, S.; Farougou, S.; Chevillon, C. Ehrlichia ruminantium infects Rhipicephalus microplus in West Africa. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faburay, B.; Geysen, D.; Munstermann, S.; Taoufik, A.; Postigo, M.; Jongejan, F. Molecular detection of Ehrlichia ruminantium infection in Amblyomma variegatum ticks in The Gambia. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2007, 42, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorusso, V.; Wijnveld, M.; Majekodunmi, A.O.; Dongkum, C.; Fajinmi, A.; Dogo, A.G.; Thrusfield, M.; Mugenyi, A.; Vaumourin, E.; Igweh, A.C.; et al. Tick-borne pathogens of zoonotic and veterinary importance in Nigerian cattle. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, M.; Veir, J.K.; Shropshire, S.B.; Lappin, M.R. Ehrlichia canis in dogs experimentally infected, treated, and then immune suppressed during the acute or subclinical phases. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2020, 34, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoust, B.; Bourry, O.; Gomez, J.; Lafay, L.; Casali, F.; Leroy, E.; Parzy, D. Surveys on seroprevalence of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis among dogs living in the Ivory Coast and Gabon and evaluation of a quick commercial test kit dot-ELISA. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1078, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medkour, H.; Laidoudi, Y.; Athias, E.; Bouam, A.; Dizoe, S.; Davoust, B.; Mediannikov, O. Molecular and serological detection of animal and human vector-borne pathogens in the blood of dogs from Cote d’Ivoire. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 69, 101412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roqueplo, C.; Cheminel, V.; Bourry, O.; Gomez, J.; Prevosto, J.M.; Parzy, D.; Davoust, B. Canine ehrlichiosis in the Ivory Coast and Gabon: Alteration of biochemical blood parameters based on Ehrlichia canis serology. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2009, 15 (Suppl. 2), 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.C.; Zweygarth, E.; Ribeiro, M.F.; da Silveira, J.A.; de la Fuente, J.; Grubhoffer, L.; Valdés, J.J.; Passos, L.M.F. New species of Ehrlichia isolated from Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus shows an ortholog of the E. canis major immunogenic glycoprotein gp36 with a new sequence of tandem repeats. Parasit. Vectors 2012, 5, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Meng, C.; Gao, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tang, G.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Zhou, G.; Wang, W.; et al. Diversity of Rickettsiales in Rhipicephalus microplus ticks collected in domestic ruminants in Guizhou Province, China. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2024 Copyright by Authors. Licensed as an open access article using a CC BY 4.0 license.